-40%

1892-97 Mary Bayard, Wife of USA Ambassador to Great Britain to Sir M Dillon

$ 95.97

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

1892-97 Mary Bayard, Wife of USA Ambassador to Great Britain to Sir M DillonThis product data sheet is originally written in English.

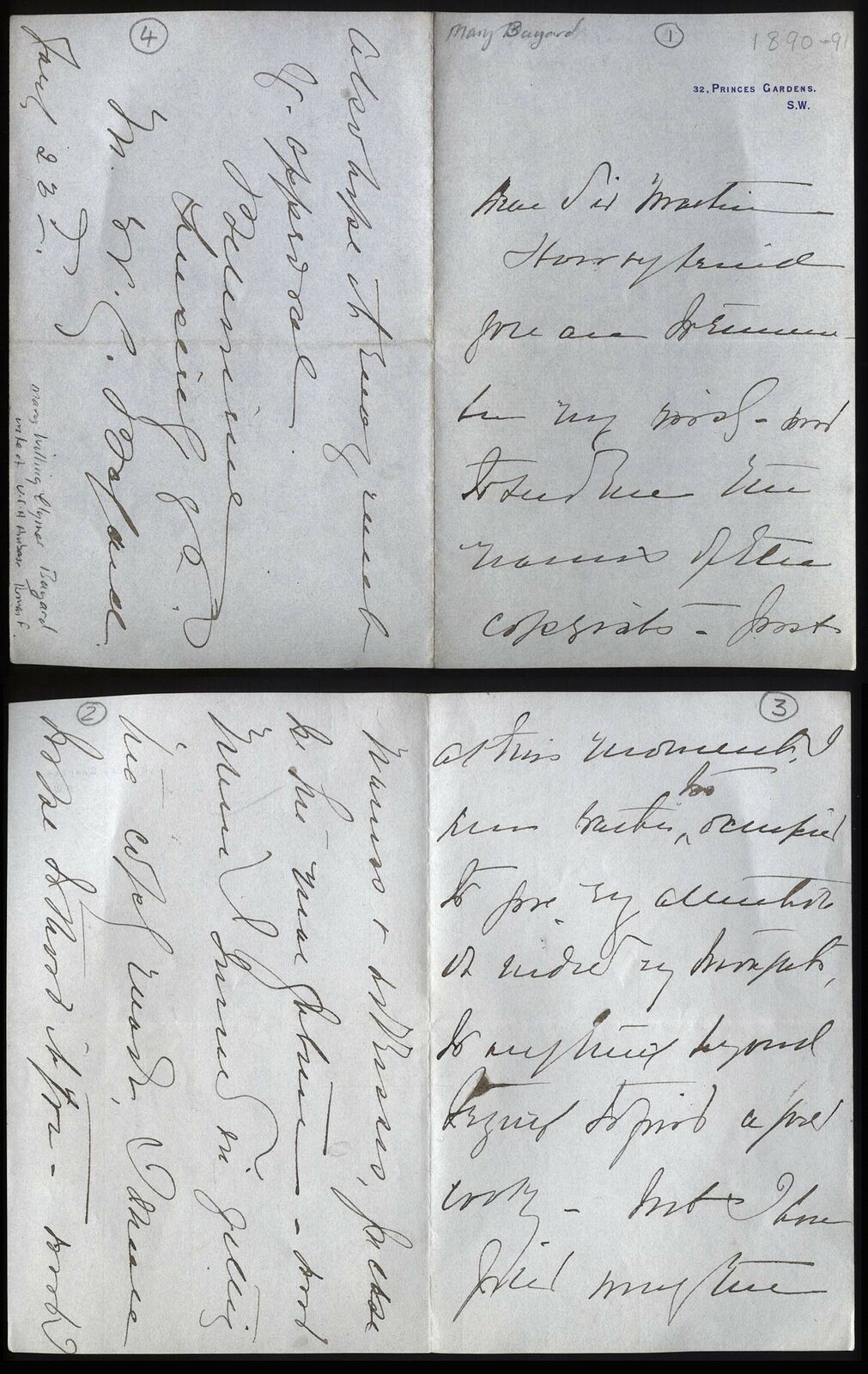

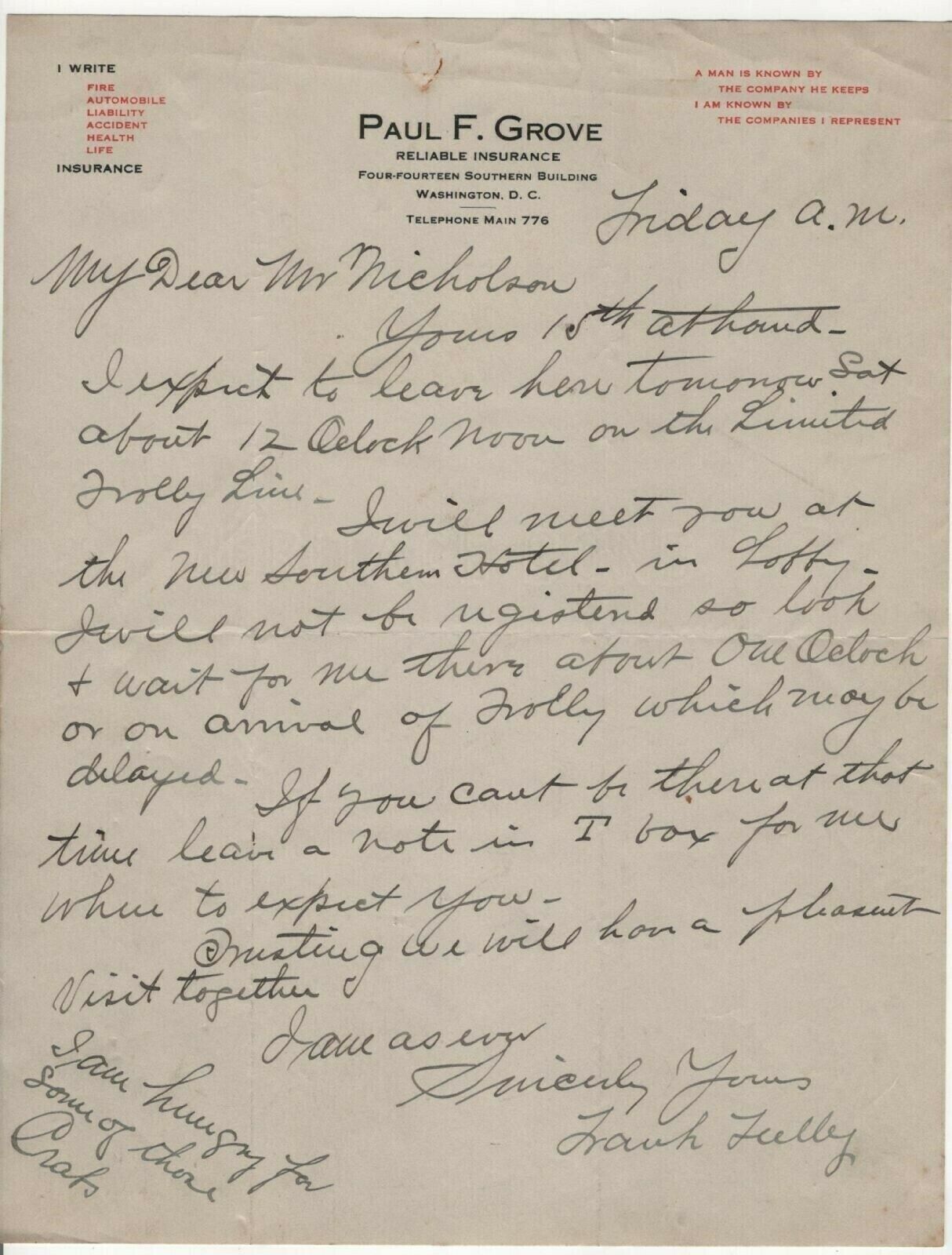

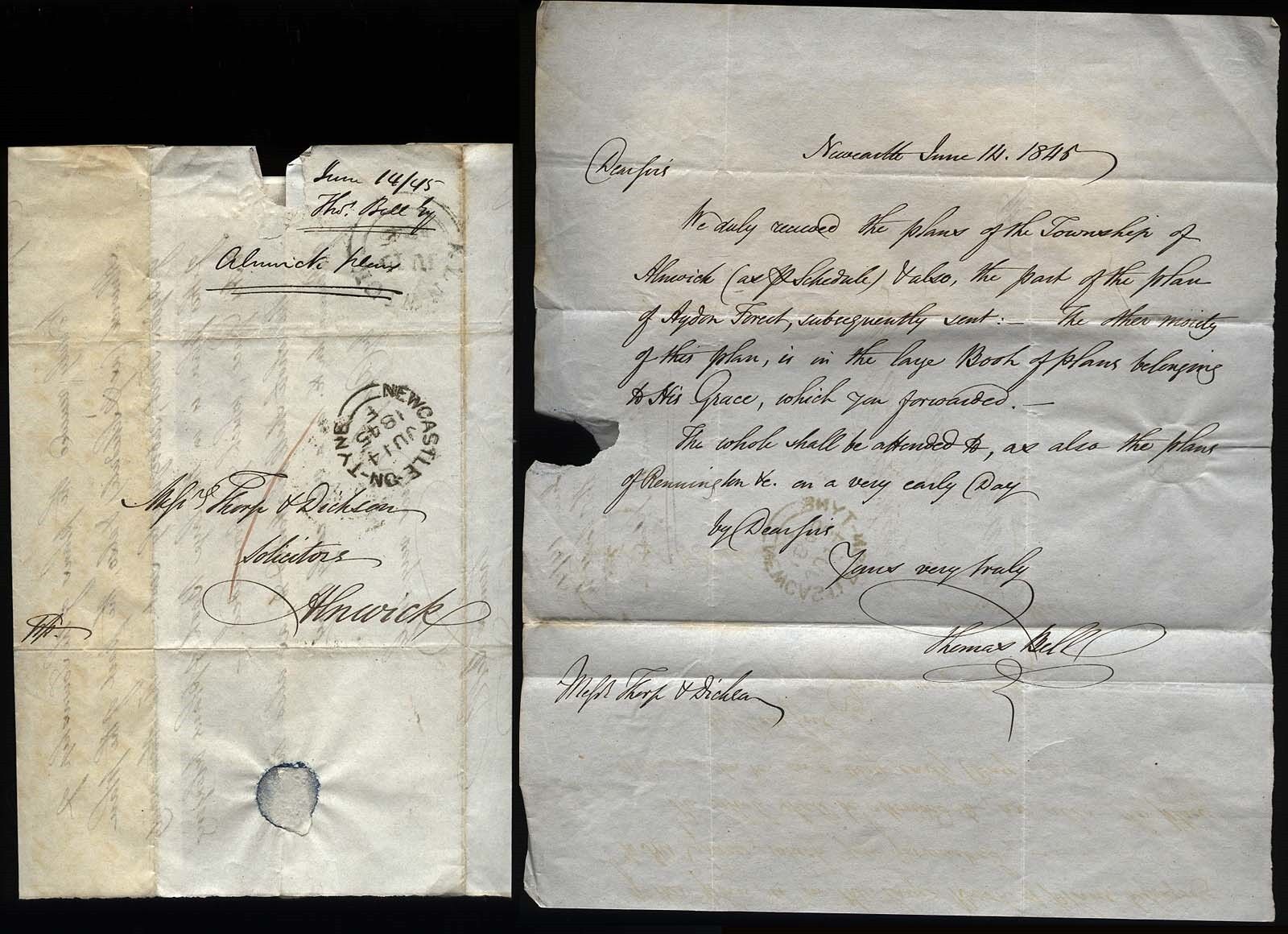

1892-97 Mary Willing Clymer Bayard, Wife of USA Ambassador to Great Britain, Thomas Francis Bayard, two letters from her at their home 32 Princess Gardens. S.W. to General Sir Martin Dillon.

Thomas Francis Bayard (October 29, 1828 – September 28, 1898) was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat from Wilmington, Delaware. A Democrat, he served three terms as United States Senator from Delaware and made three unsuccessful bids for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States. In 1885, President Grover Cleveland appointed him Secretary of State. After four years in private life, he returned to the diplomatic arena as Ambassador to the United Kingdom.

Born in Delaware to a prominent family, Bayard learned politics from his father James A. Bayard Jr., who also served in the Senate. In 1869, the Delaware legislature elected Bayard to the Senate upon his father's retirement. A Peace Democrat during the Civil War, Bayard spent his early years in the Senate in opposition to Republican policies, especially the Reconstruction of the defeated Confederacy. His conservatism extended to financial matters as he became known as a staunch supporter of the gold standard and an opponent of greenbacks and silver coinage which he believed would cause inflation. Bayard's conservative politics made him popular in the South and with Eastern financial interests, but never popular enough to obtain the Democratic nomination for president which he attempted to win in 1876, 1880 and 1884.

In 1885, President Cleveland appointed Bayard Secretary of State. Bayard worked with Cleveland to promote American trade in the Pacific while avoiding the acquisition of colonies at a time when many Americans clamored for them. He sought increased cooperation with Great Britain, working to resolve disputes over fishing and seal-hunting rights in the waters around the Canada–United States border. As ambassador, Bayard continued to strive for Anglo-American friendship. This brought him into conflict with his successor at the State Department Richard Olney, when Olney and Cleveland demanded more aggressive diplomatic overtures than Bayard wished in the Venezuelan crisis of 1895. His term at the American embassy ended in 1897 and he died the following year.

Early life and family

Bayard was born in Wilmington, Delaware in 1828, the second son of James A. Bayard Jr. and Anne née Francis.[1] The Bayard family was prominent in Delaware as Bayard's father would be elected to the United States Senate in 1851. Among Bayard's ancestors were his grandfather James A. Bayard, also a Senator; and great-grandfather Richard Bassett, who served as Senator from and Governor of Delaware.[2] Several other relatives served in high office, including Bayard's uncle Richard H. Bayard, another Delaware Senator; and his great-great-uncle Nicholas Bayard, who was Mayor of New York City.[2] On his mother's side, Bayard descended from Philadelphia lawyer and financier Tench Francis Jr.

Bayard was educated in private academies in Wilmington and then in Flushing, New York, when his father moved to New York City for business reasons.[3] Bayard's father returned to Delaware in 1843, but he remained in New York, working as a clerk in the mercantile firm of his brother-in-law August Schermerhorn.[3] In 1846, his father secured him a job in a banking firm in Philadelphia and he worked there for the next two years.[4] Bayard was unsatisfied with his progress at the firm and returned to Wilmington to read law at his father's office.

Bayard was admitted to the bar in 1851,[5] the year his father was elected to the United States Senate.[a] Thomas took on greater responsibilities in the family law office and rose quickly in the legal profession.[6] In 1853, after the election of Democratic President Franklin Pierce, Bayard was appointed United States Attorney for Delaware.[7] He spent only a year in the position before moving to Philadelphia to open a practice with his friend William Shippen, a partnership that lasted until Shippen's death in 1858.[7] While in Philadelphia, Bayard met Louise Lee, whom he married in October 1856. The marriage produced twelve children.

Civil War and Reconstruction

espite his rebukes at the Democratic national conventions in 1876 and 1880, Bayard was again considered among the leading candidates for the nomination in 1884.[94] Tilden again was ambiguous about his willingness to run, but by 1883 New York's new governor, Grover Cleveland, began to surpass Tilden as a likely candidate.[94] After Tilden definitively bowed out in June 1884, many of his former supporters began to flock to Bayard.[95] Many Democrats were concerned with Cleveland's ability to carry his home state after he, like Tilden before him, became embroiled in a feud with the Tammany Hall wing of the party.[96] At the same time, the Tammany Democrats became more friendly to Bayard.

By the time the Democrats had assembled in Chicago on July 8, 1884 to begin their convention, the Republicans had already picked their nominee: James G. Blaine of Maine. Blaine's nomination turned many reform-minded Republicans (known as Mugwumps) away from their party. Bayard and Cleveland, seen as honest politicians, were the Democrats most favored by the renegade Republican faction.[98] Bayard was optimistic at the start of the convention, but the results of the first ballot ran heavily against him: 170 votes to Cleveland's 392.[99] The reason was the same as in 1880: as Congressman Robert S. Stevens of New York said, "I believe if he were President his Administration would be one in which every American citizen would take pride. I believe he is a patriot, but it would be a suicidal attempt to nominate him. His [1861] Dover speech would be sent into every household in the North."[100] The voting the next day demonstrated the point, as Cleveland was nominated on the second ballot.

The resulting campaign between Cleveland and Blaine focused more on scandal and mudslinging than the issues of the day.[101] In the end, Cleveland eked out a narrow victory. Carrying New York was crucial for the Democrat; a shift of just 550 votes in that state would have given the election to Blaine.[102] Instead, Cleveland carried his home state and a Democrat was elected president for the first time since 1856. Cleveland recognized Bayard's status in the party hierarchy by offering him the top spot in his cabinet: Secretary of State.[103] Bayard did not think himself an expert in foreign affairs and enjoyed the sixteen years he had spent in the Senate; even so, he accepted the post and joined the administration.

espite their agreement on Samoa, much of Bayard's term of office was taken up in settling disputes with Great Britain. The largest of these concerned the Canadian fisheries off the Atlantic coasts of Canada and Newfoundland.[g][112] The rights of American fisherman in Canadian waters had been disputed since American independence, but the most recent disagreement stemmed from Congress's decision in 1885 to abrogate part of the 1871 treaty that governed the situation.[112] Under that treaty, American fishermen had the right to fish in Canadian waters; in return, fishermen from Canada and Newfoundland had the right to export fish to the United States duty-free.[112] Protectionists in Congress thought the arrangement hurt American fisherman, and convinced their colleagues to repeal it. In response, Canadian authorities fell back on an interpretation of the earlier Treaty of 1818, and began to seize American vessels.[113] In 1887, the lame duck 49th Congress then passed the Fisheries Retaliation Act, which empowered the president to bar Canadian ships from American ports if he thought Canadians were treating American fishermen "unjustly;" Cleveland signed the bill, but did not enforce it and hoped he and Bayard would be able to find a diplomatic solution to the escalating trade war.

Britain agreed to negotiate, and a six-member commission convened in Washington in June 1887.[115] Bayard led the American delegation, joined by James Burrill Angell, president of the University of Michigan, and William LeBaron Putnam, a Maine lawyer and international law scholar.[116] Joseph Chamberlain, a leading statesman in the British Parliament, led their delegation, which also included Lionel Sackville-West, the British ambassador to the United States, and Charles Tupper, a future Prime Minister of Canada.[116] By February 1888, the commission agreed on a new treaty, which would create a mixed commission to determine which bays were open to American fishermen. Americans could purchase provisions and bait in Canada if they purchased a license, but if Canadian fisherman were allowed to sell their catch in the United States duty-free, then the Americans' licenses to fish in Canada would be free.[114] Bayard believed that the treaty, "if observed honorably and honestly, will prevent future friction ... between the two nations."[117] The Senate, controlled by Republicans, disagreed, and rejected the treaty by a 27–30 vote.[118] Aware of the risk that the treaty might be rejected, Bayard and Chamberlain agreed on a two-year working agreement, allowing Americans to continue their fishing in Canadian waters by paying a fee. This arrangement was renewed every two years until 1912, when a permanent solution was found.

A similar dispute with Britain arose in the Pacific, over the rights of Canadians to hunt seals in waters off the Pribilof Islands, a part of Alaska.[120] While only Americans had the right to take seals on the islands, the right to hunt in the waters around them was less well-defined, and Americans believed foreign sealers were depleting the herd too quickly by hunting off-shore. Bayard and Cleveland believed the waters around the islands to be exclusively American, but when Cleveland ordered the seizure of Canadian ships there, Bayard tried to convince him to search for a diplomatic solution instead.[120] The situation remained unresolved when the administration left office in 1889, and remained so until the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention of 1911.

Relations with Britain were also impaired when Sackville-West intervened in the 1888 election. A Republican, posing as a British immigrant to the United States, asked Sackville-West whether voting for Cleveland or his Republican opponent, Benjamin Harrison, would best serve British interests. Sackville-West wrote that Cleveland was better for Britain; Republicans published the letter in October 1888, hoping to diminish Cleveland's popularity among Irish-Americans.[122] Cleveland's cabinet discussed the matter and instructed Bayard to inform the ambassador his services would no longer be required in Washington. Bayard attempted to limit the electoral damage, and gave a speech in Baltimore condemning Republicans for scheming to portray Cleveland as a British tool.[123] Cleveland was defeated for re-election the following month in a close election.[124]

Return to private life

Bayard's term as Secretary of State ended in March 1889 after Cleveland's defeat, and he returned to Wilmington to resume his law practice. He lived in "very comfortable circumstances" there, with a fortune estimated at 0,000, although his income from the law practice was modest.[h][126] His wife having died in 1886,

Bayard remarried in 1889 to Mary Willing Clymer, the granddaughter and namesake of the Philadelphia socialite Mary Willing Clymer

Bayard remained involved with Democratic politics and stayed informed on foreign affairs.[126] When Cleveland was re-elected in 1892, many assumed Bayard would resume his position in the cabinet.[127] Instead, Cleveland selected Judge Walter Q. Gresham of Indiana for the State Department and appointed Bayard Ambassador to Great Britain, the first American envoy to Britain to hold that rank (his predecessors had been envoys).[128] Bayard accepted the appointment, which the Senate quickly confirmed.

Ambassador to Great Britain

Bayard, as depicted in Vanity Fair in 1894 while ambassador to Britain On June 12, 1893, Lord Rosebury, the British Foreign Secretary, received Bayard in London.[130] Bayard began his tenure as ambassador with an "instinctive feeling of friendship for England," and a desire for peace and cooperation between the two nations.[131] That desire was quickly impaired when Cleveland took the side of Venezuela when that nation insisted on taking a boundary dispute between it and British Guiana to international arbitration. The exact boundary had been in dispute for decades, but Britain had consistently denied any arbitration except over a small portion of the line; Venezuela wished the entire boundary included in any arbitration.

Bayard spent mid-1894 in the United States conferring with Gresham. The tension in the Venezuelan boundary dispute continued to escalate, while British disagreements with Nicaragua also threatened to involve the United States.[133] Britain had once ruled the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua (the Mosquito Coast) but had abandoned it in 1860.[134] Nicaragua had annexed the area while guaranteeing the inhabitants (the Miskito people) a degree of autonomy.[134] When Nicaragua expanded their control of the area in 1894, the Miskito chief, Robert Henry Clarence, protested with the support of the British ambassador.[135] Bayard agreed with Cleveland and Gresham that the British were not attempting to reestablish their colony, but Nicaraguans (and many Anglophobic Americans) saw a more sinister motive, including a possible British-controlled canal through Nicaragua.[136] Returning to England, Bayard met with the new Foreign Secretary, Lord Kimberley, to emphasize Nicaragua's right to govern the area.

The tension over Nicaragua soon abated, but the May 1895 death of Secretary Gresham, who like Bayard had favored cooperation with the British, led to increased disagreement over the Venezuela issue.[138] Cleveland appointed Richard Olney to take over the State Department, and Olney soon proved more confrontational than his predecessor. Olney's opinion, soon adopted by Cleveland, was that the Monroe Doctrine not only prohibited new European colonies, but also declared an American national interest in any matter of substance within the hemisphere.[132] Olney drafted a long dispatch on the history of the problem, declaring that "to-day the United States is practically sovereign on this continent, and its fiat is law upon the subjects to which it confines its interposition ..."[139] Bayard delivered the note to the British Prime Minister (Lord Salisbury, who was also serving as Foreign Secretary) on August 7, 1895.

Olney's note was met with vehement disagreement and delay, but when tempers cooled, the British agreed to arbitration later that year.[141] Bayard disagreed with the bellicose tone of the message, which he attributed to an effort to satisfy Anglophobia among "Radical Republicans and the foolish Irishmen."[142] Olney, for his part, thought Bayard soft-pedaled the note and asked Cleveland to remove Bayard from office, which Cleveland declined.[143] The House of Representatives agreed with Olney, and passed a resolution of censure against Bayard in December 1895.[144] Britain and Venezuela formally agreed to arbitration in February 1897, one month before the Cleveland administration came to an end. The panel's final judgement, delivered in 1899, awarded Britain almost all of the disputed territory.

Death and legacy

Thomas Bayard statue in Wilmington, DelawareBayard remained in London until the arrival of his successor, John Hay, in April 1897.[146] He returned to Wilmington that May and visited ex-President Cleveland at his home in PRINCETON the following month, remaining friendly with him despite their differences on the Venezuela question.[146] Bayard's health had begun to decline in England, and he was often ill after his return to the United States. He died on September 28, 1898, while visiting his daughter Mabel Bayard Warren in Dedham, Massachusetts.[147] Bayard was buried in the Old Swedes Episcopal Church Cemetery at Wilmington. He was survived by his second wife and seven of his twelve children, including Thomas F. Bayard Jr., who would serve in the United States Senate from 1922 to 1929.

Thirteen years after his death, the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica said of Bayard that "his tall dignified person, unfailing courtesy, and polished, if somewhat deliberate, eloquence made him a man of mark in all the best circles. He was considered indeed by many Americans to have become too partial to English ways; and, for the expression of some criticisms regarded as unfavorable to his own countrymen, the House of Representatives went so far as to pass ... a vote of censure on him. The value of Bayard's diplomacy was, however, fully recognized in the United Kingdom where he worthily upheld the traditions of a famous line of American ministers."[5] In 1929, the Dictionary of American Biography described Bayard, as a Senator, as being "remembered rather for his opposition to Republican policies ... than for constructive legislation of the successful solution of great problems", and said that he had "the convictions of an earlier day ... and was never inclined, either politically or socially, to seek popularity with the country at large."[149] Charles C. Tansill, a conservative historian, found much to praise in Bayard; he published a volume on Bayard's diplomatic career in 1940 and another about his congressional career in 1946, the only full-length biographies to appear since Bayard's death. Later historians took a dimmer view of Bayard's diplomatic career; in a 1989 book, Henry E. Mattox numbered Bayard among the Gilded Age foreign service officers who were "demonstrably incompetent."[150]

In 1924, Mount Bayard, a mountain in southeast Alaska was named in his honor

:

Powered by SixBit's eCommerce Solution

1892-97 Mary Willing Clymer Bayard, Wife of USA Ambassador to Great Britain, Thomas Francis Bayard, two letters from her at their home 32 Princess Gardens. S.W. to General Sir Martin Dillon. Thomas Francis Bayard (October 29, 1828 – September 28, 1898) was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat from Wilmington, Delaware. A Democrat, he served three terms as United States Senator from Delaware and made three unsuccessful bids for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States. In 1885, President Grover Cleveland appointed him Secretary of State. After four years in private life, he returned to the diplomatic arena as Ambassador to the United Kingdom. Born in Delaware to a prominent family, Bayard learned politics from his father James A. Bayard Jr., who also served in t

Related Interests

United States Ambassador

EAN

Does Not apply

Country

England

Family Surname

Baynard

City/Town/Village/Place

London

England County

Middlesex

Era

1891-1900

Addressed to

General Sir Martin Dillon

Document Type

Original Manuscript Letter

Year of Issue

Circa 1892-97

Street Location

32 Princess Gardens S.W.